North Tyne Charity Cup 1949-50

By Clive Dalton

‘Association Football’ was the main sport

in the North Tyne from at least the 1800s for working class folk, as the rules

were simple, little equipment was needed, and the game was easy to organise. Supporting the big national teams such

as Newcastle United and Sunderland, where players like Jackie Milburn (Wor

Jackie) were cult figures, maintained interest and

ambitions for the local lads.

Different villages that could muster enough

young men to take the sport seriously were keen to compete in the competition for

The North Tyne Charity Cup. These

were Associated Football Clubs (AFC) from Kielder (Kielder Hearts), Falstone, Tarset, Bellingham, Wark,

Barrasford, Simonburn and Acomb.

Humsaugh didn’t field a team so the village lads played for other

village teams, which was a common practice.

There’s little record of the competition’s history, or where

the actual cup is now and the photo below of the 1949-50 final may be one of

few survivors of those times. Graham

Batey now aged 90, is the only surviving member of the young men in the

photograph he proudly framed and kept over the years.

Graham said he didn’t play in the first losing

match of the season, when Bellingham were beaten 10-0 by Barrasford, but he did

play at Inside Left then Outside Left after returning from National Service in

the RAF in Hong Kong. Bellingham won the cup by beating Barrasford 2-1. The

village GP Dr Kirk presented the cup and he would have brought many of the

players (including Graham) into the world.

Graham joined the family building firm with

his father and Uncle Arthur, founded by his grandfather Joseph Batey. They built and repaired many of the

houses in Bellingham and the North Tyne valley over a very long period.

Jim Irwin holding the cup in the photo was the

captain. The team didn’t have an official coach, although Graham says Matt

Sisterson, a village notable, gave him some personal coaching.

The older men in the photo were ‘the

committee’. Ernie Scott, who ran a grocer’s shop in the village as well as a

van to extend the business was secretary, and Jack Maughan, chief cashier of

Lloyds Bank was treasurer. Graham

remembers Jack being very proud of the 50 pounds Sterling he banked from one

notable match. Entry was sixpence

for an adult and children were free- so they’d had a great turnout with a crowd

of 2000!

Bellingham played on the Show Field where

the roadside shed could be used for changing if needed, and for spectators to

file through to pay. And there was the enormous advantage of the grandstand for a good view and shelter.

The committee used to have a weekly meeting

during the season in the Black Bull hotel, even though some were staunch

Methodists like Graham’s father George and uncle Arthur Batey, with alcohol not

on their menu. Graham reckons it

would be the only time his father went into a pub in the village, where there

was plenty of choice among the four pubs to support! The framed photo hung in the Black Bull to be admired for many years Graham said.

Graham can’t remember the Cup being

sponsored by any one source, but the Club must have raised enough funds (probably

mainly from gate takings) to provide the jerseys, shorts (called knickers) and boots for the

players. Travel to other venues

was provided by local bus.

Bellingham played in black and yellow shirts.

The ball in those days unlike today’s light

plastic valve-inflated balls was made of strong leather sections stitched

together. Inside was a rubber

bladder, which after blowing up through a tube was tied off and folded back

inside the ball. A lace then kept this in place across the entrance like lacing

up a boot, which was memorable whenever you headed the ball which ended up

being very heavy, especially when wet!

So putting more air into the ball was always a mission.

Graham cannot remember who took the team photograph,

which is interesting as it would have needed a camera with large film or more

likely a glass plate. Certainly the standard Kodak Box Brownie of the time

would not have coped. The only person around at the time with the appropriate

equipment would have to be the noted professional village photographer Frank

Collier who had his shop, studio and darkroom in Lockup lane in the village. But

the caption on the photo is not his familiar backhand style, but could have been

done by an assistant.

Newcastle United

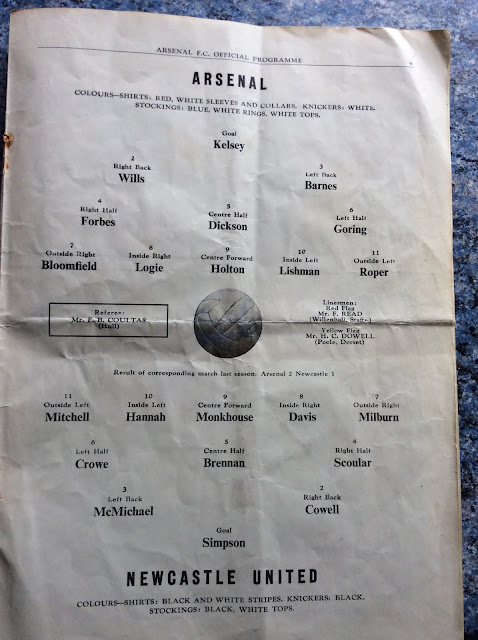

'Wor Jackie' was the player everybody knew, and John McPhail, who I sat beside in primary school and we both failed our 11+ exam on the same day, had gone to a match (Newcastle United versus Arsenal) in London in 1954 while doing his National Service. He actually got Wor Jackie's autograph on the back of an envelope, but had it stolen years later while in the Merchant Navy. Note there are no African names in the teams.

Newcastle United

'Wor Jackie' was the player everybody knew, and John McPhail, who I sat beside in primary school and we both failed our 11+ exam on the same day, had gone to a match (Newcastle United versus Arsenal) in London in 1954 while doing his National Service. He actually got Wor Jackie's autograph on the back of an envelope, but had it stolen years later while in the Merchant Navy. Note there are no African names in the teams.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to Graham Batey of Lynn

View, Fountain Terrace, Bellingham for the photograph and information. Thanks also to John McPhail for the programme copy. April 2019